Living in Hell under the Eyes of Buddha

By Meng Sokhouy

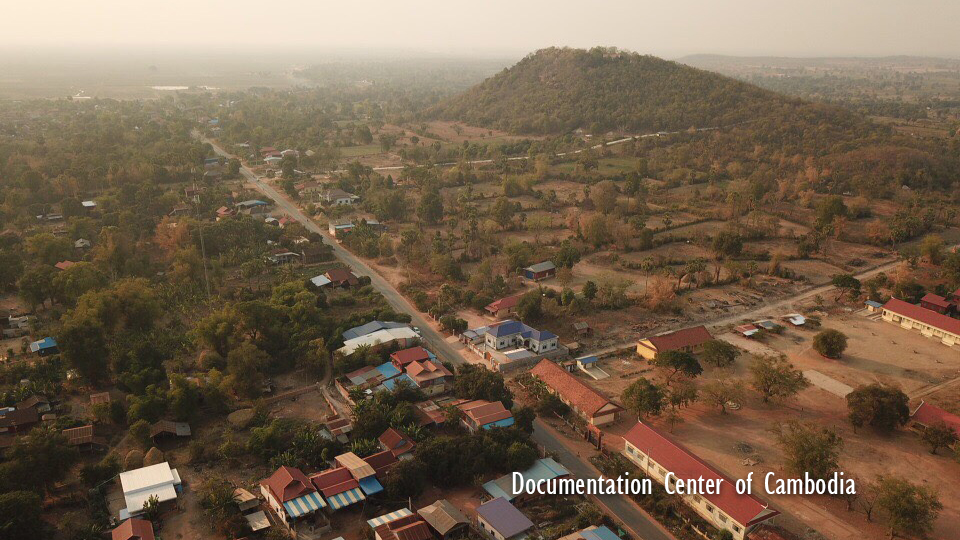

A Story from Former Khmer Rouge Region 5

My day-to-day life was like while forced to labor for the Khmer Rouge

I was 14 in 1975. In describing what life was like during the Khmer Rouge regime, the first word that comes to mind is the word isolation.

Everyone looked the same from haircut, skin color, and clothing, and we all talked the same, but everyone was also completely on their own. You could not trust anybody, even your own family members or closest friends, because everyone had to look out for themselves. Isolation permeated everyday life and it really fit in with the Khmer Rouge goal of complete control over the population.

On a more practical level, life was reduced to the most primitive level. Time didn’t exist. No one had clocks or watches, so time was regulated by the rising and setting of the sun, the rooster, and however, the Khmer Rouge wanted to organize the day. I would get up with the sun and work in the field until the first 15-minute meal break. Food would consist of a watery rice porridge and at least in Region 5, we were only given two spoons of water a day during hot season because clean water was scarce.

Our clothes were in tatters and we had no shoes. If we wanted to wash our clothes, we would wash them in a basket. The day would be dominated by forced work in the fields, accompanied by different communist songs played over the loudspeaker. When the evening came, we would receive another quick serving of soup followed by a long session of individual confessions. Everyone had to confess a mistake they had made every evening to the collective—from missing your mother to thinking about Coca Cola or bread.

The confessions were another instrument of control. If the Khmer Rouge leader liked you, then you were forgiven, but if he did not, then your mistake could be determined to be a crime, at which point you could be taken away and beaten or killed. Every night without the moon was also filled with thoughts of escape. People always tried to escape at night for practical reasons and some people were successful, but other were not and they were arrested.

It’s hard to imagine this kind of life today—where there is no toilet, toothbrush, soap, shoes, or any of the amenities that seem so basic to human life. My sisters did not have hygiene products and if you became sick, you had a serious risk of dying because there was no medical care. Many people died from exhaustion or during the hot season, the rain, would invite sickness. This is what day-to-day life was like and it lasted approximately four years.